Quit Your Day Job: How Josh Godwin left his life behind for 3 months on the Eastern Divide (Part 1)

Next week, Part 2 will be published and sent to paid subscribers of the blog. Please consider supporting our programming with a tax-deductible $9 monthly subscription! See below to subscribe. (If you can't see the big green box below this text, try opening this article in your browser)

Part One

“I Worked Ten Years For A Life I Didn’t Want”

Cameron: Josh, who are you and how did you end up here, having just ridden a bike thousands of miles down the Eastern Divide?

Josh: My name is Josh. Long story short, I spent about ten years in the automotive industry. For the first four or five years, I thought that was it. I thought that job would get me a house, help me settle down, give me that normal life a lot of people in our age range grew up imagining: property, house, family, the usual.

Over time, a bunch of things happened that pushed me out of that mindset and eventually out of that life. Some of it was personal stuff, some of it was the industry itself. It all added up to this feeling that maybe a “normal” life was not actually mine.

Cameron: What were those moments that broke the white-picket-fence picture for you?

Josh: In 2020 I was diagnosed with testicular cancer. I had surgery, luckily no chemo, but it shook me. I was working, paying medical bills, just trying to figure out what I wanted my life to look like after that.

People sometimes find that kind of story inspiring, like “you went through this thing and now you can help others.” For me, it mainly forced me to ask hard questions. I realized I could not just coast through life waiting for some payoff down the road.

At the same time, I was waking up to what the automotive business really was. It is a very money-driven industry. There are a lot of people who rely on you to make them money. I started doing extra things trying to move up: recruitment at job fairs, being in promotional videos, being the “face” of the shop side on YouTube.

For a while, I thought I was building a career. After a few years I realized I was being used. I was doing all this extra work and not really seeing any benefit. That sank in slowly, and it felt terrible. Almost like a depression. Nobody wants to feel like they are just a tool.

Cameron: And this was all while you were still at the dealership?

Josh: Yeah. Around 2020 it really came to a head. I ended up out of work for about a month on short-term disability. That time gave me a lot of room to think.

Through coworkers I found out my manager had said things like “don’t give him a raise, let him work himself out of here.” Comments like that. Hearing that when you are doing your best hurts. It made it clear I was not being looked after, no matter how hard I tried.

I was also burning out. Before 2020, I might burn out, take a couple weeks off, then bounce back. After 2020, the burnout became serious. I would have whole months where I did not want to go to work, did not want to be in that environment at all.

I ended up in therapy for about a year and a half. I was trying to understand my neurodivergence. I am pretty sure I am on the spectrum. That played into the burnout too. I am very routine-oriented, I care a lot, and I throw myself into things. If the environment does not fit, it grinds you down.

Cameron: Same here on the neurodivergent side. And yet you stayed another five years.

Josh: That is the thing. I knew I needed to leave, but I was stuck in the routine. I had been there so long I did not know anything else. After 2020 I spent about five more years in that same cycle. Telling people “I’m going to get out of this job” and never making the jump.

Then there was everything happening in the world. Housing costs went up. I ended up in some credit card debt just trying to keep my head above water. That made it even harder to walk away. I kept thinking: I can not leave, I have to pay this, I have to cover that.

In early 2024 I left a long-term relationship. We had moved in together. I learned a lot in those two years: how I show up in relationships, what I do well, what I need to do better. Later in 2024, my dog of nine years passed away. That one hit very hard. By the end of 2024, mentally, I was in a rough place.

Hatching a Plan

Cameron: When did the idea for the trip appear?

Josh: Probably a month after my dog passed. Suddenly the responsibilities I had been carrying dropped away. It became just me. I still had debt, but that was it.

Around October 2024 I decided I was done talking about changing my life and I was actually going to do it. I set a date: end of July. That gave me about nine months to grind. From October through late July I worked as much as I could, paid off my debt, and put around five thousand dollars into savings.

The plan was to ride a long-distance bikepacking route. At first I wanted to do the Continental Divide. The season for that is roughly July through October or November, so July made sense as an exit date.

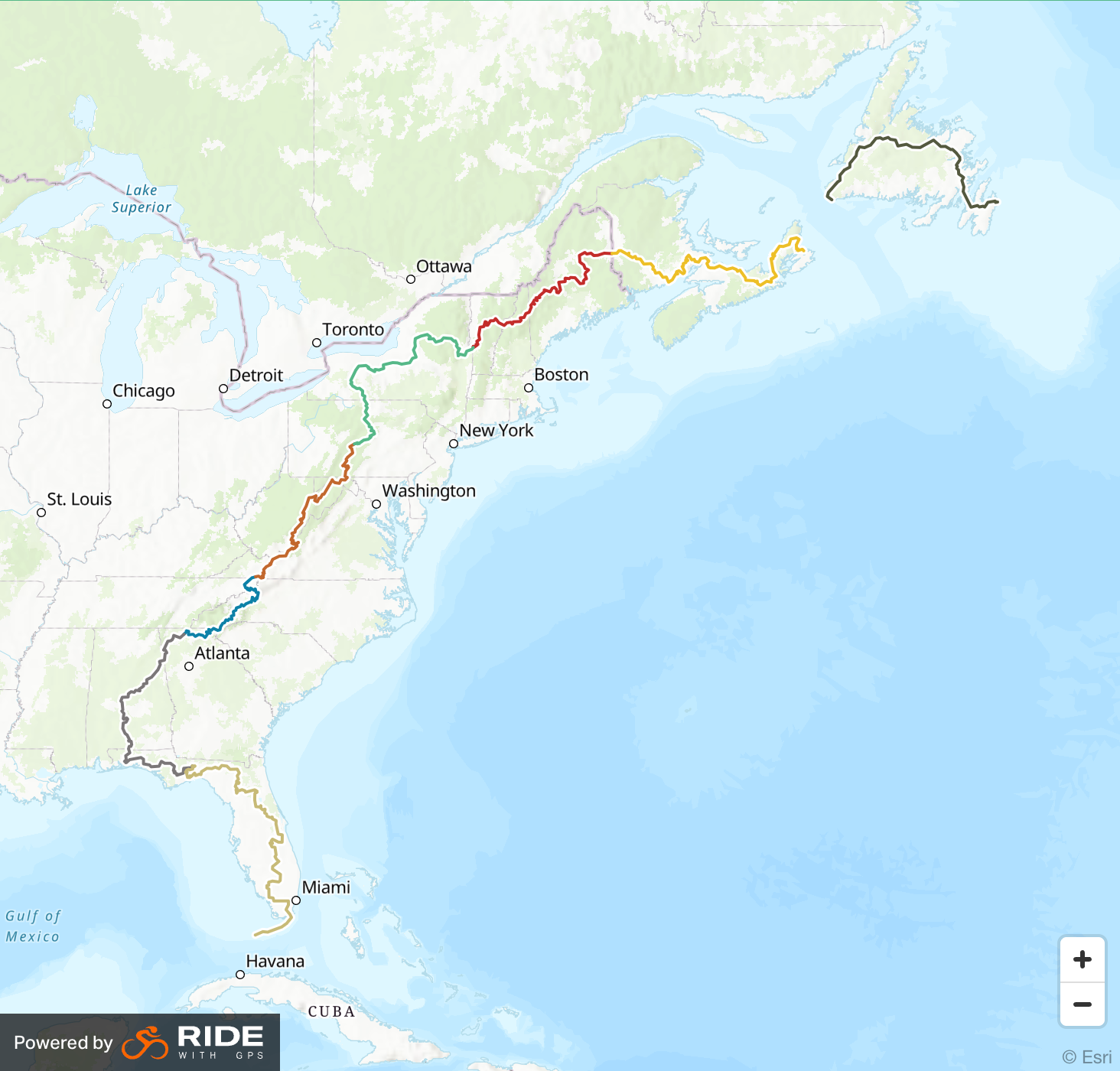

Later I shifted to the Eastern Divide Trail, which runs from Newfoundland down to Key West. I decided that would be my route. End of July, I would leave the job and go.

Cameron: So October rolls around, you pick July as your exit, you put your head down and go.

Josh: Yeah. The date is what kept me honest. For about six months it was just work, save, plan, build the bike, collect gear. Six months is not enough time for a trip like this, and I know that now, but at the time I figured I could make it work.

That final week at work was surreal. I had told my manager and some coworkers what I was going to do, partly to hold myself accountable. It felt like closing one era and opening another.

Packing was surreal too. I went out, got a big box, broke down the bike, and packed it days before the flight. I had not flown since I was maybe five years old, so honestly the airport stressed me out more than the trip. The timelines, security, all the “official” stuff. My mom joked that I was more worried about TSA than riding across a continent.

It is a very neurodivergent thing. I am routine-based and very particular about time, interviews, serious stuff like that. I am the guy who shows up way too early for everything.

The Trip Begins

Cameron: So you pack the bike, get on a one-way flight, and land in Newfoundland.

Josh: I flew into St. John’s, Newfoundland. The official starting point for the Eastern Divide is Cape Spear, just outside of town. It is the easternmost point in North America. There is a sign, a lighthouse, trails along a cliff that drops straight to the ocean. You literally cannot go any farther east.

I got there a couple of days early. Day one was building the bike and riding around St. John’s. It is a really beautiful little maritime town, full of fishing boats, bars, and old bunkers. I spent that day making sure the bike felt right. The second day was resupply and logistics. I wanted to start riding first thing the next morning, so I gave myself time to gather my thoughts.

On the morning I rode out to Cape Spear, I biked about sixteen miles from St. John’s. That was my first real wake-up call on climbing. It was my first fifteen or sixteen percent grade for a mile or two, on a loaded single-speed mountain bike. I remember thinking, “Oh, this is going to be serious.” I was standing in the pedals, walking sections, just doing whatever I could to get over the hill.

Getting to the Cape itself was emotional. You are standing on a cliff over the Atlantic, next to this sign that says you are at the most eastern point of North America, and you know you are about to point your wheel toward Key West. I spent a couple of hours at the lighthouse, wandering around, drinking a smoothie, just letting it sink in. Months of grinding at work, years of frustration, and now this huge reset.

Cameron: When you look back at who you were standing at Cape Spear and who you are now, what changed?

Josh: A lot. I am not stressed about things the way I used to be. I am staying at my mom’s house right now. I did take on some debt from the trip and I have bills to pay, but it does not weigh on me the same way.

My idea of space changed. I do not feel like I need an apartment anymore. Give me a ten-by-ten room and a twin mattress and I am good. Life got simpler.

I also learned how much other people’s emotions do not need to run my life. When I was saving for the trip, I was working late, grabbing the higher paying jobs, doing everything I could to stack money. Some people at the dealership hated that. It is a flat-rate culture, so if you are doing well, someone thinks you are stealing their work.

At first I cared a lot about what they thought. Over time I realized their jealousy was not my problem. I care about people making money and being okay, but I do not have to shrink my life to keep someone else comfortable.

The other big thing was anxiety. Before the trip, something like an airport felt huge. Now, after months of navigating fires, reroutes, border crossings, and long stretches of nowhere, walking into an airport feels like a drop of water in a bucket.

Cameron: What did those first days of riding look like? Tire-dip in the ocean, ceremonial start, that sort of thing?

Josh: I wish. Cape Spear is basically a cliff. There is no friendly little beach to roll your wheel into. You are standing a hundred feet above the water.

So my start was more like: ride out there, sit with the moment, look at the lighthouse, then roll away from this big cliff. I was so eager I did about ninety miles that first day, which might have been a mistake, but I was just excited. I ended up at this beautiful campsite next to a little stream, pitched the tent, and felt like I was really out there.

Day two, the reality of logistics set in. I got weirdly intimidated about finding a campsite. There are plenty of places in Newfoundland where you can just stealth camp, and that is what locals and other riders do. There are snowmobile cabins, open land, all of that. But in my head I was thinking, “I do not know this place. I do not know the rules.” So after about eighty miles I bailed to a hotel via the highway.

Newfoundland was my learning ground. I was treating that first week like a vacation. I had just worked ten straight years. I was riding, but I was also wandering, figuring out how I wanted to travel. I was underbiked. Most of Newfoundland is on this rail trail called the T’Railway. It is not like our mellow rail trails in North Carolina. It is rough, built for snowmobiles, ATVs, and UTVs. On a rigid 26-inch single speed, chunks of it were barely rideable. I was getting off, pushing through rocks, just trying to keep moving.

All told, it took about twelve or thirteen days to get from St. John’s to Port aux Basques on the western side of the island. Then I hopped a ferry to Nova Scotia.

Cameron: That is about twelve days in. What happened when you hit Nova Scotia?

Josh: The ferry from Port aux Basques to North Sydney, Nova Scotia is an all-day thing. I camped a few miles outside town, rode into the ferry early in the morning, then spent eight or nine hours on the boat. By the time I got off, I basically just rolled to a hotel and used it as a resupply and reset point.

Wildfires and Reroutes

That is where the first big curveball hit. This was August. There were wildfires in New Brunswick and another one starting in southern Nova Scotia. There was even a fire back in Newfoundland. I started checking the news and realized this was serious. The Canadian government ended up passing an order banning “unnecessary wilderness travel.” The fines were huge, something like fifty thousand dollars.

I am sure some riders still went through. For me, as a foreigner, it felt like a bad idea to gamble with that. The official route would have taken me up into Cape Breton and then back down across northern Nova Scotia, which meant a lot of remote land that might have been closed or unsafe.

So I scrapped the official track and built my own. That was a theme of the trip. The Eastern Divide is still new and there are sections that are not fully ironed out yet.

In Nova Scotia I spent a couple hundred miles riding a mix of back roads, the Trans-Canada Highway in spots, and quiet country routes along long lakes. I crossed this tiny cable ferry, stumbled onto a reconstructed Scottish settlement on a hill overlooking a huge lake, spent a day wandering around while people in period clothes did demos. It was one of those things that was nowhere in my original plan, but I am glad I rerouted. After the remoteness of Newfoundland’s rail trail, it was nice to be on pavement with towns and little places to stop.

Cameron: And then the fires caught up with you again.

Josh: Exactly. As I got closer to New Brunswick I started seeing haze. There were fires to the north and south and my planned path would run between them. I was already riding in some smoke and I did not like that at all.

So I made another call. I took a ferry to Prince Edward Island, which is not on the Eastern Divide route. If anyone wants incredible, low-stress riding, PEI is amazing. They have this grid of resurfaced old wagon roads. They feel like rail trails, very flat, very smooth, and you ride through farmland and rolling countryside.

I spent two or three days there, ended up in Charlottetown, and then faced the same question: do I push back into the fire zone or do I protect my lungs and my health for the long term? I chose health. I caught a bus from Charlottetown to Woodstock, New Brunswick, which is about fifteen miles from the U.S. border.

That decision was hard. I sulked about it. I had a similar feeling in Nova Scotia when I first left the official route. I really wanted to be able to say I followed the Eastern Divide exactly. But eventually I realized this is what a big adventure looks like. You make it your own. Nobody else is there with you in that moment. Nobody else is breathing the smoke. You have to do what feels right.

Crossing the Border

Cameron: So you get to Woodstock, roll down toward the U.S. border, and finally cross back into the States.

Josh: Yeah. I rode from Woodstock to the border one day and then from the border to Houlton, Maine the same day. I kept it short because I did not know what to expect from the crossing. I figured Customs might have a lot of questions about a guy on a loaded bike.

The crossing ended up being pretty chill. I just lined up with the cars like anyone else. The officer looked at me and asked, “What are you doing?” I told him I was trying to ride down the East Coast and we had a short conversation. He said someone had come through not long before doing something similar. Then he radioed someone, waved me through, and that was it.

As soon as I got across the border there is a bridge where the Eastern Divide route passes over I-95. I was riding up that bridge when I met Scott, another rider doing the route. He had already done the southern section and was now working north-to-south on this part, trying to connect it.

We were basically neck and neck from then on. Not riding together every day, but leapfrogging. Sometimes we would camp in the same place and swap stories or share tips about the route. Sometimes we would both want our own space. It was nice having a trail friend appear right at the border. It made the transition into New England feel less lonely.

Comments ()